Biogeography is the area of biology that studies the geographic distribution of organisms and the reasons why they occur (or don’t) on certain places of the Earth. Traditionally it has two approaches: the historical, focusing on larger temporal and spatial scales, relating the present distribution pattern with evolutionary processes (e.g.: speciation by vicariance), and the ecological biogeography, that studies how ecological processes, such as climate, altitude and other environmental agents affects the distribution, usually taking into account a short time interval and small areas. But can we assume that there is a clear division of the biogeography?

Ratite’s biogeographical distribuction explained by the continental drift.

For a long time the climate was considered to be the best factor to explain the organisms’ actual distribution, but with a better understanding of biological interactions and processes, it became obvious that only one characteristic couldn’t explain the current pattern of species occurrence, causing some researchers to criticize the ecological biogeography. But it isn’t just because the climate isn’t a variable that explains everything that we can disregard the effect of other landscape components on the delimitation of the biological distribution, seeing the diversity of niches that we have in the present.

As an example, some abiotic factors, like substrate characteristics, can define the distribution of gastropods in Britain and echinoderms in Colombia; it all depends on the scale that we are working with (maybe the substrate doesn’t mean anything when we are analyzing the global distribution of gastropods). And this is just one of many ecological factors that takes part on the delimitation of an organism’s area of life: even ecological interactions and behavioral differences can create an non-physical barrier that constrains the dispersal.

Interacting with these ecological processes we have historical ones, like vicariance and the landscape changes (e.g.: orogeny and volcanism) that shaped the present habitat diversity, and created many ecological niches, making it hard to discern between these two approaches.

In other words, ecological processes do define species spatial distribution, but many landscape characteristics resulted from long-time geological mechanisms. If we see biogeography like this, can’t we say that the ecological biogeography is kind of consequence of the historical? That could be true in the past, but now we have an important landscape modifying agent: the human being.

The age we are in, the Anthropocene, habitat modifications that would take centuries to occur naturally can happen in less than a decade, and it may even cause speciation or hybridization in some cases, like with the crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) and the hoary fox (Lycalopex vetulus). Those two canids most likely hybridized by induction of the deforestation of the Atlantic Forest (alteration of natural habitats), connecting both species. So we’re having a process usually related with the historical biogeography, occurring in a short time period, caused by an alteration of the landscape of an area.

Lycalopex vetulus (left) and Cerdocyon thous (right).

Seeing how the two divisions of biogeography are increasingly merging, we should expect more researches considering both the historical and ecological approaches at the same time, or even as if they were one.

Literature:

Garcez, F. S. 2015. Filogeografia e história populacional de Lycalopex vetulus (Carnivora, Canidae), incluindo sua hibridação com L. gymnocercus. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Curso de Zoologia, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul, 2015. Available on: http://repositorio.pucrs.br/dspace/handle/10923/7711. Access on: 10 abr. 2017.

Haila, Y. 2002. A conceptual genealogy of fragmentation research: from island biogeography to landscape ecology. Ecological Applications, 12(2), 321–334.

Heads, M. 2015. The relationship between biogeography and ecology – envelopes, models, predictions. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 115, 456–468.

Monge-Nájera, J. 2008. Ecological biogeography: a review with emphasis on conservation and the neutral model. Gayana 72(1), 102-112.

Santos, C.M.D. & Amorim, D.S. 2007. Why biogeographical hypotheses need a well supported phylogenetic framework: a conceptual evaluation. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia, 47(4): 63-73.

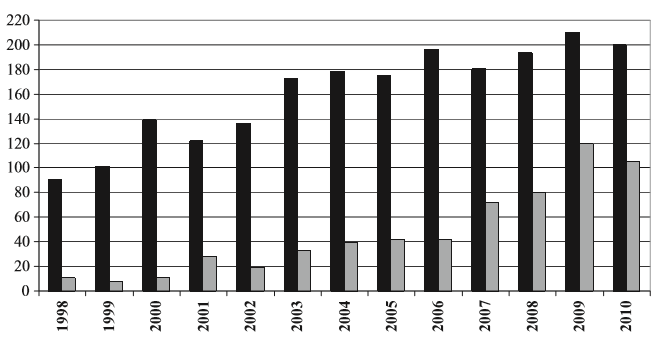

Number of articles published in each volume of the Journal of Biogeography during 1998–2010 (total = black bars; historical biogeography = gray bars) (Posadas et al., 2013).

Number of articles published in each volume of the Journal of Biogeography during 1998–2010 (total = black bars; historical biogeography = gray bars) (Posadas et al., 2013). Percentage of papers authored by one (black bars), two (diagonal line bars), three (horizontal line bars), and four or more authors (gray bars) per year. Trend lines added for papers authored by a single author (black) and by four or more authors (gray) (Posadas et al., 2013).

Percentage of papers authored by one (black bars), two (diagonal line bars), three (horizontal line bars), and four or more authors (gray bars) per year. Trend lines added for papers authored by a single author (black) and by four or more authors (gray) (Posadas et al., 2013). Distribution of papers applying the five most used approaches per year (Posadas et al., 2013).

Distribution of papers applying the five most used approaches per year (Posadas et al., 2013).