Life is not easy. It may not always be okay. The history of Life also had ups and downs like a roller-coaster, some moments with a great turn up of diversity and some moments with a breathtaking fall. Literally. These moments of abrupt decline in diversity are called mass extinctions when most species disappear.

Not all species survive the journey.

There is usually a normal rate of extinctions in Nature. This rate is called background extinction. Some species are extinguished by natural factors. However, mass extinctions are events in which at least half of the lineages are extinguished in a short period of time. Recalling that “short” on the geological scale can mean up to 15 million years. These events mark an important change in the formation of the biota. There were five big events of this size and they were called “Big Five”. The end of the Ordovician (440 m.y.a) and the end of the Devonian (375 m.y.a) had extinctions caused by glaciations; the extinctions of the end of Permian (250 m.y.a) and the end of the Triassic (200 m.a.a.) were caused by great volcanic activity; the famous extinction of the late Cretaceous (65 m.y.a.) was caused by the impacts of meteorites.

The geological eras. Pterosaurs not included.

The image of a destructive meteor is a very common in the popular imaginary, although it was officially proposed only in 1980. Despite this extinction that decimated the dinosaurs to be more striking, the mass extinction of the Permian was the worst of all. Between 80-90% of all species that existed died, ecosystems such as forests and corals were decimated and the Life as we know it almost got eliminated. Important lineages like sea scorpions and trilobites disappeared. This was the most dangerous time to go on Earth, but we survived.

R.I.P. – Rest in Permian

Illustrations of the past eras point too dramatic titles such as “age of the fishes”, “age of the dinosaurs”, “age of men” as if it were a succession of which team is winning. In fact, we are still in the “age of bacteria” that remains surviving all extinctions. There were still bacteria in the Ordovician, there were fish in the Jurassic, and there were birds in the Eocene. There are no evidences about obligatory progress and gain of complexity, it is just survival. In 5/6 of the history, Life was unicellular and interpreting large animals as powerful survivors is a bias of human observation. Diversity today is a consequence of several lineages that have survived in their own way, changing some anatomic details. There were several Noah’s arks going through mass extinctions. The ark of the vertebrates still survives since the Cambrian, but some of us ended up being left behind.

When bacteria ruled the Earth

Mass extinctions also bring an important lesson in humility. It does not matter much your skills, you need to be lucky. Chance plays a large role in the survival of species. A hairy lineage would do very well if the climate changed in a great glaciation, but would be bad if the climate changed to a desert. And it would certainly not matter if he lived in the slopes of an erupting volcano. It’s not always blind luck: large, rare, ultra-specialist species restricted to one local becomes an easier target. But there are no precise answers. Chance also causes the winners. Mammals coexisted with dinosaurs for 100 million years until a meteor exterminated the best competitors. And the dinosaurs themselves were already decreasing in the meteor epoch. In addition, a lineage of dinosaurs also survived the meteor, diversified and took advantage of the extinction of others: the birds. Birds are dinosaurs that survived, not for its skills, but for a great portion of luck.

This is not how good luck is achieved

Life is a branched pattern of ephemeral components in which lineages matter more than the represents. This is a story punctuated by tragedies, but always (for now) recovered the roles, even if it is with new actors. We are living in a time of great loss of diversity. In the Anthropocene, the nowadays age, there are destruction of ecosystems, global warming, pollution, and unbridled hunting. In relation to birds, we have lost 1.3% of all known species in the last 500 years. This rate is 26 times bigger than a normal background extinction rate. Apocalypse Now. Whether it is or not a sixth mass extinction (now, by our fault) it does not matter. We must confront the problem of loss of a large number of species in a much faster period. With the knowledge of the other extinctions we can guard us against what can happen. Our species is here for a time crumb and we can be extinguished much more easily than many other ex-winners. Trilobites, dinosaurs, Ammonites, they all reigned much longer than humans. If we do not put ourselves in our place, soon we will be in another.

“Those who cannot remember the past, are condemned to repeat it”

References:

Benton, Michael J., and Richard J. Twitchett. “How to kill (almost) all life: the end-Permian extinction event.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 18.7 (2003): 358-365.

Gould, Stephen Jay. “The evolution of life on the earth.” Scientific American 271.4 (1994): 84-91.

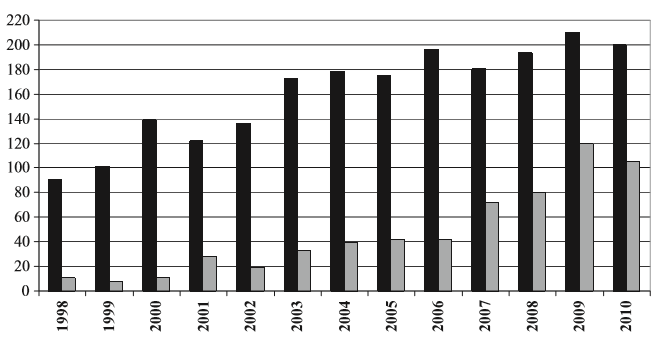

Number of articles published in each volume of the Journal of Biogeography during 1998–2010 (total = black bars; historical biogeography = gray bars) (Posadas et al., 2013).

Number of articles published in each volume of the Journal of Biogeography during 1998–2010 (total = black bars; historical biogeography = gray bars) (Posadas et al., 2013). Percentage of papers authored by one (black bars), two (diagonal line bars), three (horizontal line bars), and four or more authors (gray bars) per year. Trend lines added for papers authored by a single author (black) and by four or more authors (gray) (Posadas et al., 2013).

Percentage of papers authored by one (black bars), two (diagonal line bars), three (horizontal line bars), and four or more authors (gray bars) per year. Trend lines added for papers authored by a single author (black) and by four or more authors (gray) (Posadas et al., 2013). Distribution of papers applying the five most used approaches per year (Posadas et al., 2013).

Distribution of papers applying the five most used approaches per year (Posadas et al., 2013).